Videos

James S. Jackson Symposium Recording – December 1, 2023.

Memories and tributes from colleagues and friends

The abiding memory that we have of James is his unique combination of generosity, thoughtfulness, and consistent astoundingly high quality contribution to our research endeavours. We are three academics based in the UK who worked on a number of international studies with James over a 20 year period, but here we want to say more about the person we had the privilege and pleasure of working with, rather than the work itself. We each met James in different ways. One of us, James Nazroo, sent an out-of-the-blue message to him, and other members of Michigan faculty, asking whether we could meet up during a visit to Ann Arbour to discuss shared interests. James was the only one to reply to this approach from an unknown and relatively early career scholar, and not only arranged a meeting, but also a visit to meet members of his research group and an invite to an informal get-together that was happening in James and Toni’s home. Another of us, Saffron, remembers a first visit to Ann Arbor to discuss a paper that we were beginning to work on with James and Myriam Torres, when, rather than expecting her to get a cab to Ann Arbor on the evening of her arrival at Detroit, James met her at the airport and drove her to her hotel. And the third of us, Laia, remembers not only a very positive interaction with James when he examined her PhD, but also when, during one of her visits to Ann Arbor, as she was walking along the street a car pulled up, James jumped out to make sure things were ok with her, and then arranged to take her out for dinner the next day. And our interactions with James (and Toni) during his visits to London and Manchester were of a similar vein. He met our families, played with our children, watched them grow and socialised with them. Toni may remember James Nazroo’s daughters, aged seven and five, explaining the plot of Snow White to her J. They both, some twenty years later, still have very fond memories of James and Toni. We, and our other colleagues who met and worked with James, all found him to be warm, open, supportive and very generous with his time and resources – he invested in us and we learnt a great deal from him.

There are so many memories, dating back to when James first came to the University and began his long association with ISR. Jerry and I, along with the Zajonc family, became in those early years a place where James came at night to relax and talk. Who was he then? As always, full of ideas, animated, related in his unique way of tuning into us as well as sharing who he was, and apparently never needing sleep. Jerry and I, much older than James, were parents of young children who awakened ready for the day by six in the morning. Those evenings with James that sometimes went on into the early am were a stretch for us, but we never tired of them. James’ knock on the front door was an invitation to talk about politics, both within the university and the country at large, to share our lives, and soon to begin to hear him talk about the importance of mounting a true national study of African Americans.

What was so important about such an idea? The standard national survey of the United States never produced enough African Americans, given their proportion in the country, to carry out analyses of the life experiences of African Americans of many different ages, who held different kinds of jobs, and who lived in different parts of the country. At best at that time, the Survey Center occasionally oversampled African Americans but even that produced just a

limited depiction of their variation, as did the existence of measures that had been standardized with the white population in the country and did not begin to capture the cultural, geographic, and social class richness of the African American population.

Shortly after James came to UM, he, Belinda Tucker, and Jerry worked with graduate students to frame the first National Study of Black Americans and then implemented it, piloting new measures and new interviews techniques, mounting the first national African American interviewing staff to carry out the study, and analyzing the data that formed the dissertations of numerous students and the initial publications of what has become a treasure trove of knowledge about the African American population.

James, although not much older than this initial group of graduate students, ran an organized, effective, vibrant collective on the fifth floor of ISR. It was before the internet, of course, and so everyone was at ISR at night, long into the night. There were also parties and dances, some at our house where we removed furniture, often sharing dancing parties with the Chicano Study graduate students and with the faculty and students of the Social Psychology Program. Those were amazing times – optimistic about social change and efficacious about producing it.

And James was the creator and guider of what became the Program of Research on Black Americans and the social scientist who I think has made the greatest impact on what we know about African Americans through his own scholarship and that of the huge number of graduate students, post-docs, other fellows, and colleagues across the country.

James’ kindness, compassion, and caring along with his engaging soft-spoken fireceness in pursuit of truth and justice made for an alive, purposeful, and enjoyable research and learning environment that I feel so fortunate to have experienced firsthand. Many, many thanks, James.

I don’t think James Jackson was on time for anything. That was because he was so garrulous. It could take him forty-five minutes to walk from the psychology department in East Hall to ISR. And he wasn’t there yet…. He had to get from the front door of ISR upstairs to RCGD. But you must understand the number of students and friends asking for advice along the way, the number of deals brokered, how much he enjoyed catching up on the sports scores and casual conversation. This is what made James the great mentor he was. But it gave his secretary fits trying to keep a schedule, placating students and faculty competing for his time. It was all in a day’s work though and so well worth it!

Working for James Jackson was to be independent, credited for your contributions, trusted, given responsibility and respected for your work. It was meeting interesting people and well-known academics everyday, being involved in stimulating and informative conversations. It was to be in a happy workplace where we were encouraged to produce but to break up the work with fun to keep it real.

James was a true visionary, constantly coming up with new ideas which we, staff and faculty, were charged with implementing (sometimes a challenging project). But it was his insight and indefatigable energy that kept all those around him moving forward.

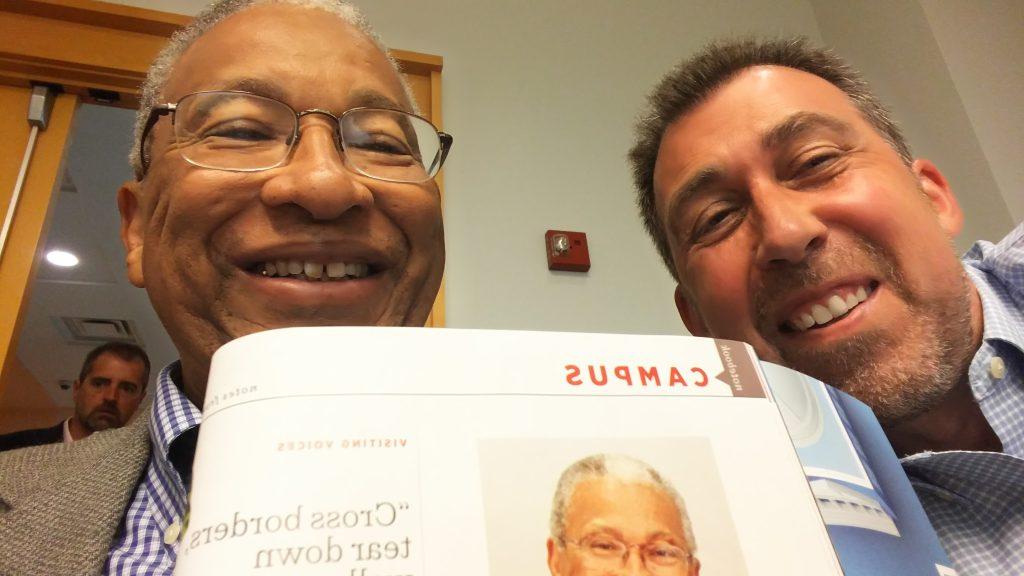

I had the honor of serving as co-director (I’m at Wayne State) of the Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research with James from 1998-2020 (am now serving with Robert Taylor). These are a few pictures of James at our Healthier Black Elders Center events (our community core of the MCUAAAR P30 grant).

The first time I met Dr. James Jackson was an experience imprinted upon my mind; a moment woven with the threads of destiny. Introduced to me by my esteemed dissertation advisor, Dr. Harriette McAdoo, our meeting was destined to shape the course of my academic journey. With generosity rare to find, Dr. Jackson graciously shared the transcripts of the NSBA racial socialization questions data, a treasure trove that immensely enriched my dissertation research. Later, acting on Dr. McAdoo’s sage advice, I applied and merited the National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Program for Research on Black Americans. It was here that I truly got to witness the magic of Dr. Jackson’s mentorship.

To merely call James an ‘exceptional mentor’ would be a disservice. He was the embodiment of mentorship in its truest form. His dedication was evident in the selfless hours he committed to providing guidance and support. In him, I saw a beacon for teaching, research, and outreach – his methods, a gold standard I continually aspire to emulate. What was even more remarkable was Dr. Jackson’s enduring commitment. His mentorship wasn’t limited by time or constrained by phases of academic progression. He stayed with his mentees, guiding them beyond graduation, shaping not just their academic pursuits but also carving paths for their futures. With Dr. Jackson, it was never about mere productivity. It was about elevating his mentees, pushing us to scale heights we hadn’t even dreamt of. His presence assured us that we could surpass our own expectations, for he saw in our potential that we sometimes failed to recognize. As I reflect upon the monumental impact Dr. James Jackson had on my life; I am filled with profound gratitude. For he was not just a mentor, but a guiding star, illuminating my path in academia and beyond.

I started working as a researcher within the Program for Research on Black Americans (PRBA) at the Institute for Social Research (ISR) in September 2004; in this role, I worked closely with James on various research projects. And, I saw James in his role as the Director of the ISR. James was peerless, pure and simple. Reflect on his research, teaching, mentorship, and service; his scholarship was pioneering, prodigious, and voluminous. Considering the breadth of his knowledge and expertise, courageous and visionary leadership skills, passion and compassion, boundless levels of energy and generosity, talent for incubating and encouraging networks for collaboration especially among scholars of color, and tenacity regarding creating inclusive working environments, few even come close to rivaling James.

In terms of my specific interactions with James, I am extremely appreciative of James striking a perfect balance. James gave me opportunities to take key roles across the arc of the research process (grant writing, project planning, research group facilitation, analysis planning, article and report drafting) and at the same time was always available to provide advice and support along the way. It was fun working with James and I learned a tremendous amount! Can’t ask for more than that!

I am sure that I am echoing others when I say that I am in awe of James’ inter-disciplinary, path breaking, and ambitious research agenda. Launched when James was still a junior faculty member, the National Survey of Black Americans (NSBA) challenged the notion that the over- sampling of blacks in a handful of urban areas provides sufficient representation in national surveys. The development of the WASP was simply brilliant and has been implemented internationally when sampling low-density populations. And relatedly, the NSBA makes the case that it is theoretically valid to analyze a single race group to the exclusion of whites as a comparison group. James extended this work in creative and innovative ways; for example, by investigating racial attitudes and inter-group relations in Europe, James posed the interesting question of to what extent the dynamics of race and racism varies across national contexts.

The National Survey of American Life (NSAL) extended themes of the NSBA by taking seriously the notion of heterogeneity within race based on ethnicity, nativity, and immigration status in analyzing health disparities. And more recently, James engaged in work that bridged the fields of neuroscience, epidemiology, psychology, and sociology and examined the pathways through which social conditions, social and biological markers stress, including discrimination, and health behaviors influence both physical and mental health. In order to have a full understanding of health disparities, James directed attention to the need to examine the inter-relationships between physical health and mental health.

During James’ tenure as Director, the ISR community witnessed a number of exciting and positive trends. Key successes fall under the broad headings of institutional climate, the expansion of innovative funding opportunities for upcoming researchers, the strengthening and broadening the ISR’s international ties, and the launching of innovative research projects drawing on institutional ties outside of the ISR. James was committed to an open work climate that included regular events that allowed staff to meet and raise concerns with James and events aimed at fostering and celebrating diversity broadly defined. Under James’ direction, various streams of funding for graduate students and junior scholars expanded; although it smacks of cliché-level simplicity, a commitment to increased funding for upcoming scholars is vital.

I am extraordinarily grateful for having had the opportunity to know and work with James.

James Jackson Did Not Need Another Study

When I entered the Social Psychology doctoral program at the University of Michigan, James was my Advisor. Because of that, I became involved with several national survey research projects (including the National Survey of Black Americans and National Black Election Study) even before there was officially a Program for Research on Black Americans (PRBA). Many people have mentioned this previously, but it is incredible to me how James was able to take advanced doctoral students (who knew a little something about survey research) and beginning doctoral students like myself (who knew nothing about survey research) and include them in a meaningful way on the NSBA team. I marvel at the mentoring and training model he developed to train so many doctoral students in all phases of survey research.

After I completed my dissertation, I worked for several years as a research consultant in Washington, DC, but then my life took a very different path. I was involved in the non-profit world for decades but stayed in touch with James. In 2016, at a PRBA Reunion, I told James I finally had a survey research project that I was interested in conducting, and further, that it was a logical extension of PRBA. The “small” project, #WeGlobal, would examine the lives of African Americans currently living abroad. Conducting such a study was/is fraught with multiple challenges. There is no list of Americans or African Americans living abroad, nor is there agreement on the number of members of either group. Conducting a global study requires a substantial network of researchers or research institutions, far beyond what is needed for a regional survey of multiple countries. Further, African Americans living abroad are more highly educated and typically doing well. Nobody wants to fund that!

But I was convinced that the stories of African Americans abroad had to be told, and so was James. In the spring of 2017, I talked to James about the advisory committee for the project, and he seemed so interested that I hesitantly asked him if he would be interested in serving on the #WeGlobal Advisory Committee. He said, “I would be offended if you did not ask me to join.” What?!!! Of course, I wanted him to join, but he had been diagnosed with cancer at this point and really didn’t need another survey. Not only did he join, he used all his connections to help me secure funding, even though I was at another institution, for a Planning Meeting of the Advisory Committee. The meeting was held in January 2018 and was a huge success.

Unfortunately, my institution closed its Washington, DC office in August 2018, and I was out of a job. I needed a home for #WeGlobal and for myself. James moved heaven and earth to bring me to the PRBA as the Assistant Director for International Projects in September 2019. James worked to include #WeGlobal as a project under the PRBA Innovation Fund so that we could solicit individual donations, the ISR Communications team did an interview with us to be edited for various audiences, we met with the U-M Alumni Office to talk about how we could utilize the vast alumni network to assist in conducting the study, and we strategized about possible funders. We even launched the survey in April 2019, but it didn’t turn out as we expected. We only received 91 responses, although from 32 countries. Our “citizen science” approach and the use of volunteer #/WeGlobal Ambassadors in 12 countries proved ineffective. We needed significant funding to conduct such a study.

James worked tirelessly on #WeGlobal through June 2020. I am forever grateful and indebted to him for having confidence in me, bringing me back to Michigan, and all his efforts on this project. I am committed to honoring James’ legacy and faith in me and making #WeGlobal a reality.

James and I both entered the University of Michigan in the Fall of 1971 — I as a graduate student in social psychology and he as a newly minted professor and the department’s first regular African American faculty member. He was just a few years older than me and even younger than quite a few in our cohort. So, in some sense, we all grew up together. My earliest recollections are of his perpetual smile, enormous and effusive greetings, good humor, unbridled confidence, boundless energy, socio-political consciousness, a strong and enduring sense of camaraderie, and the ability to party as hardy as we students did. Having James as a mentor was more akin in those years to having a well-schooled, brilliant, and seasoned older brother – one who always knew the score without you having to explain it.

The atmosphere in social psychology and in ISR was intensely familial in those years, thanks to the considerable efforts of James, Pat & Jerry Gurin, Libby Douvan—all my amazing mentors—and others. But, towards the end of my tenure as a student when James had the brilliant and daunting idea to conduct a survey of Blacks in the U.S. (which would be the first survey of a probability sample of Black Americans), the demands of constructing and carrying out the wholly unique and demanding study drew us together in an entirely different way. And most of us are still close friends! Jerry Gurin loved to recall how he, James, and I at the midnight hour when we completed the proposal of what was to become the legendary National Survey of Black Americans, met at the Cottage Inn (then across the street) and shared an Apple Mountain (a truly decadent dessert for which they were famous at the time). I think we thought of it as a metaphor for embarking on a journey that was viewed as folly by more than a few in the ISR hierarchy. Why not eat our dessert first? Difficult as well as joyous times were to come.

The experience of being involved with the launching of such an astonishingly impactful program enriched my life in more ways than I can recount in this brief remembrance. But, the lessons learned from the burning sands of the project were not the most valuable imparted by studying and learning with James. I believe that I was his very first dissertation student, and as such, I suspect that his guidance was even more closely pursued. I learned first and foremost the meaning, the conduct, and the profound value of mentorship done right. When my own students and postdocs have conveyed their appreciation for my counsel and direction, I know that they are thanking James. As I view the magnificent accomplishments of those who were fortunate enough to work under and with James, I also see the extraordinary accomplishments of their students and mentees. James’ academic children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren have changed the practice of many areas of psychology, survey research, political science, and so many other related disciplines and fields in the social, behavioral and health sciences.

James’ legacy is truly immeasurable and I am eternally grateful to the forces that brought me to Ann Arbor at exactly the right moment in time.

- James S. Jackson Symposium Program, December 1, 2023

- Association for Psychological Science – A Conversation with James S. Jackson

- PRBA: James Jackson (1944-2020)

- The University Record: Obituary

- The American Academy of Political and Social Science Remembers Fellow James S. Jackson

- James Jackson, Who Changed the Study of Black America, Dies at 76

- Dartmouth Mourns Trustee James Jackson

- Colleagues, former students remember Professor James S. Jackson, a scholar ‘renowned for his optimism and his energy’

- Science Magazine’s Tribute

- Remembering James S. Jackson (1944–2020), (Association for Psychological Science)

- What is Systemic About Systemic Racism? A Tribute to James S. Jackson – by Shinobu Kitayama

Photos